Capital cities have a common characteristic across the globe: a central location. Think of Rome, Abuja, Tokyo, or Brasília. Even Washington D.C., while no longer so central, was at one time midway between the Northern and Southern states of the union.

The reasons are manifold. Modern-day capitals are where states’ political power reside, so ensuring even access across a state, along with a lack of favoritism often influence their development in “neutral” geographies. For multiethnic, multi-religious states like Nigeria, this is very important. Central locations also make sense for transportation and defensive reasons. A land invasion of Brasília, deep within the hills and forests of Brazil, would be a lot more difficult than the oceanfront Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s former capital.

So, when keeping these facts in mind, I’ve always wondered about London.

There’s nothing central about London. It’s at the geographic periphery of the United Kingdom (the country), Great Britain (the island), and England (the country within a country). From the heart of London, to travel to Dover at the southeastern corner of England takes two hours by car. To the northwestern most point of Great Britain takes over twelve.

Near the ocean and on the River Thames, London has historically been quite accessible from continental Europe, too. The Danes “accessed” it by sword and axe quite a few times in the 800s.1 So, why did the Crown of England and then Britain make London their capitals?

Looking Back

When England was unified in 927 AD, it had no capital, at least the modern concept of a fixed, permanent administrative center. You may read online that Winchester was England’s first capital; however, recent scholarship indicates that this was not true,2 and that power resided with a mobile Anglo-Saxon court. The capital was where the king was at that given moment—even on the toilet.

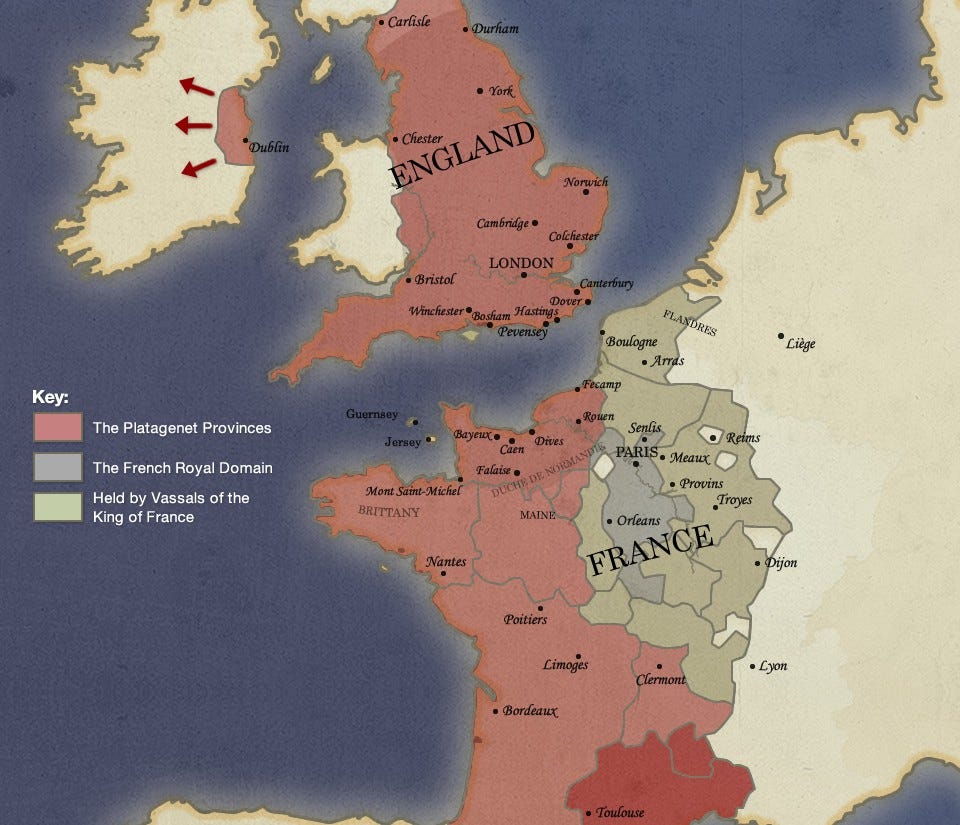

When William “the Bastard” successfully invaded England in 1066, he founded a new Anglo-Norman empire. The Normans were pretty bellicose fellows. Soon enough, they’d forged a realm that encompassed England, most of modern France, and Ireland (see the red blob below).

It’s with this context where London’s geo-strategic importance began to make sense. London provided the Norman Court a bridge between its northern and southern lands. If there was a need for the Norman king to sail to the mainland, London’s harbors provided a short hop across the English Channel. Likewise, the English Channel provided an immediate barrier between the capital and the continent.

London flourished during this period, as well. Before the onset of the Bubonic Plague, it was by far the largest city in the British Isles and one of the largest cities in Western Europe, with roughly 80,000 to 100,000 people crammed into one square mile.3 This was largely due to trade, particularly with the continent. English wool was heavily prized in the European Middle Ages,4 which resulted in a healthy export industry to the textile manufacturing centers in Flanders (modern day Belgium).

Even after the English monarchy lost its continental possessions in The Hundred Years’ War, London remained the economic and political center of the kingdom, mainly for the same reasons as listed above.

Digging Deeper

There’s more to the story than just the Norman kings of England making a geo-strategic decision, though. London’s streets and skyline today sit atop 2,000 years of history, long before the Normans or even the Anglo-Saxons arrived.

London’s origins begin with the Roman conquest of Britain, and even then, it eventually served as an administrative center. Around 47–50 AD, the Romans founded Londinium on the north bank of the Thames, near a natural crossing point of the river. The Thames provided a tidal waterway that ocean-going ships could navigate, yet it narrowed enough at Londinium to be bridged. A people famous for bridge-building, the Romans quickly threw one across the river, and from this crossing a web of roads spread out in all directions. In effect, the new settlement became the hub of a wheel—a nexus linking Britain to the rest of the Roman world.

While important in the province since its foundation, Londinium was not the original home of Roman provincial government. That honor went to Camulodunum (modern Colchester), which was an existing Brythonic settlement prior to the Roman invasion. Boudicca’s Rebellion in 60 AD changed both city’s fortunes. Her army destroyed much of the original settlement, along with Camulodunum and Verulamium (St. Albans). After the Romans won the war, their cities were left in ashes, but this gave them an opportunity to rethink their administration. Camulodunum had been out of the way and difficult to reach or resupply by water. Londinium, by contrast, was far more centrally located and convenient.

The Romans rapidly enlarged the once-modest settlement into a local Roman city—the only of its kind in the British Isles—with grand public buildings and vast markets. The wharves of Londinium brought the city wine from Gaul (modern France), olive oil from the Iberian Peninsula and Greece, and all kinds of spices from the east. In exchange, local meats and metals were exported to other ports across the Roman world.

This prosperous Roman world did not last, as we all know, and Londinium declined with the later disintegration of the Western Roman Empire. However, London revived itself, just as it did following the Bubonic Plague. The geographic and social conditions for what made London prosperous were too great for any one political or natural disaster. Hence why London today is a primate city, and one of the most influential trading centers in the world.

Barbara Højlund, “London,” Vikingeskibs Museet, https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/professions/education/the-viking-age-geography/the-vikings-in-the-west/england/london.

Ryan Lvelle, et al., Early Medieval Winchester: Communities, Authority and Power in an Urban Space, c.800-c.1200, (Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 2021), 4.

John Schofield and Alan Vince, Medieval Towns: The Archaeology of British Towns in Their European Setting, (Sheffield: Equinox Publishing, 2005), 26.

John H. Munro, "Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Textile Technology and Industrial Organisation, c. 800–1500," The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, 1 (2003a): 186-89.