Thoughts This Week - 2025/09/12

Delta Airlines, Proto-Indo-European, and finding all your notes

I had no idea that… Delta Airlines was named after the Mississippi River Delta. The world’s most profitable airline (and my favorite American carrier) started 100 years ago as a crop-dusting fleet in the South. Collett Everman (“C.E.”) Woolman, an agricultural engineer from Indiana, bought the company in 1928 and renamed it to Delta, expanding its scope of business to include passenger and mail services. The airline’s first commercial flight took to the skies in 1929, departing Dallas, Texas to arrive in Jackson, Mississippi. (Ironically, the only non-stop flights between those two locations now are on American Airlines because of the modern hub system.)

Delta’s crop dusting division continued in operation until C.E. Woolman’s death in 1966.

How do you track dead languages that were never written down?

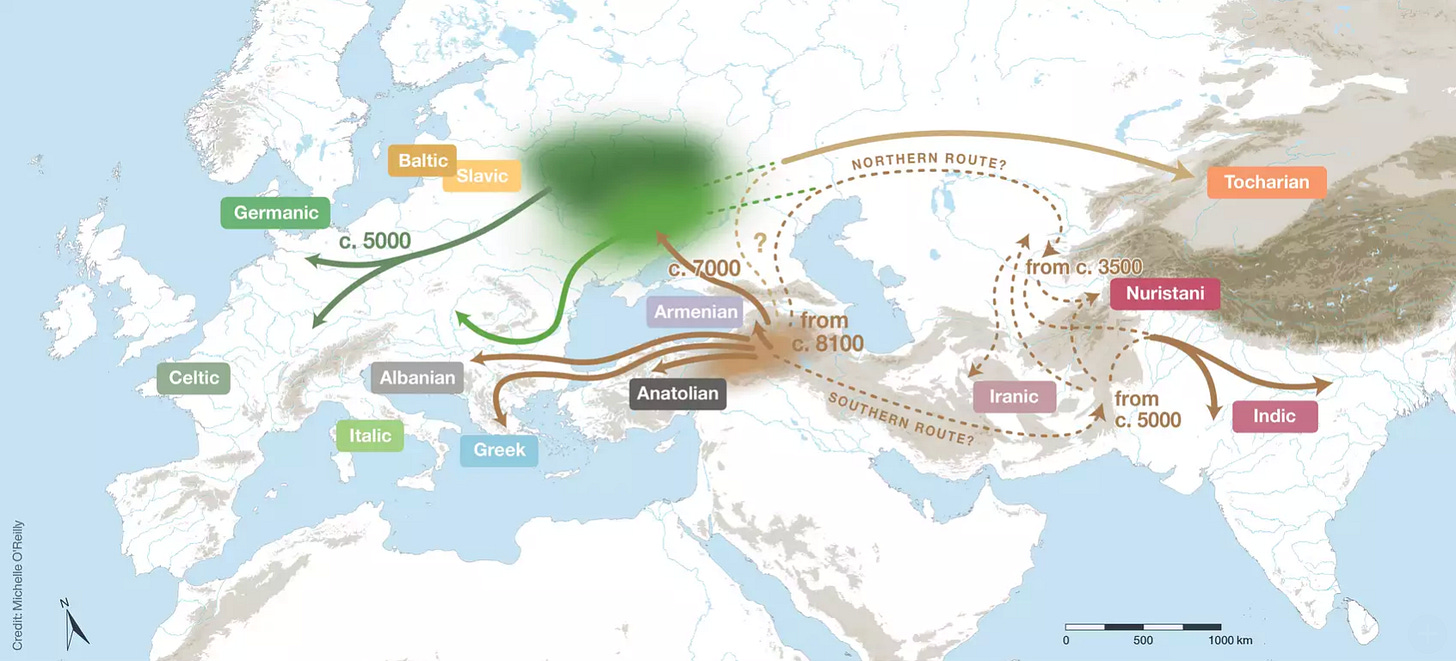

Recently, I started reading a book on the spread of Proto-Indo-European (or PIE). This is the ancestral language of the Indo-European language family (e.g., Greek, the Germanic languages, the Romance languages, the Indic languages, etc.). Linguists hypothesize that the language remained a single language from roughly 4500 to 2500 B.C., but definitive statements about PIE are difficult, given that there have been no living speakers for thousands of years and the language was never written.

So, how do we know anything about it?

The effort started from academics noticing similarities between languages across a wide geography. Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Germanic, Celtic, and Iranian languages having a common ancestor was first popularized in a 1786 speech by—and I’m not making this up—a polyglot man called William “Oriental” Jones.1 (Yikes.) Jone lived in Calcutta and, like other men of his time, noticed commonalities between Latin and Sanskrit word-pairs. Just to list a few, we have god (deus and deva), king (rex and raja), mother (mater and mata), father (pater and pita), and house (domus and dam).

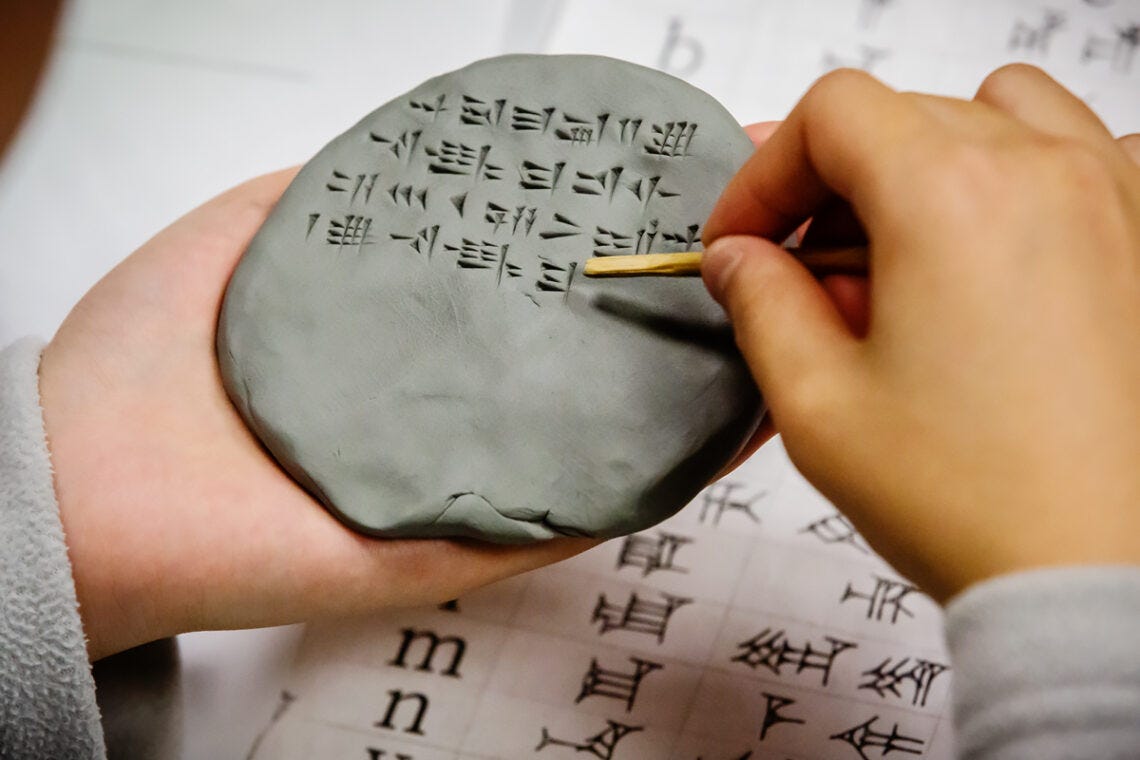

Scholars compiled ever more evidence of links between existing languages and those with written evidence, such as Latin, which led to the creation of the Proto-Indo-European hypothesis. But comparative analysis can only get us so far. Eventually, we run out of speakers and text to review.

So, returning to my original question, how do you study a language that has been dead for thousands of years? The answer is trifold: beyond linguistics, you have archeology and genetics.2

Archeology allows us to study the events of the past. What did humans eat? Where did they pick up their jewelry? Did they migrate, and if so, where? Meanwhile, geneticists can extract, sort, and interpret ancient DNA to give us insights unimaginable to the likes of William Jones and his generation of thinkers. We can see social patterns, like the elites mating within their classes, or ethnic segregation, or the speed of human migration. These innovations allow us to triangulate between fields, building a more complete picture of how language evolves.

Through triangulation, the hypothesis cited in Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global is that Proto-Indo-European was first spoken by the Yamnaya culture in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, and then spread to other parts of Eurasia over 6,000 years ago as revealed by DNA evidence. However, this is still a contested space. Linguist Paul Heggarty and a team of researchers in Leipzig, Germany published a different argument in 2023 that PIE emerged even earlier around 8100 BC, south of the Caucus Mountains.

I’m no expert and can’t weigh in on the validity of the different arguments, but I find reading them so fascinating. It makes me wonder what future generations of researchers will gleam about prehistoric languages like PIE.

Never lose a note again

I’ve been taking daily notes since February 23, 2021. It was a habit that I started during the lockdown days to help keep me sane, and I’ve stuck with it.

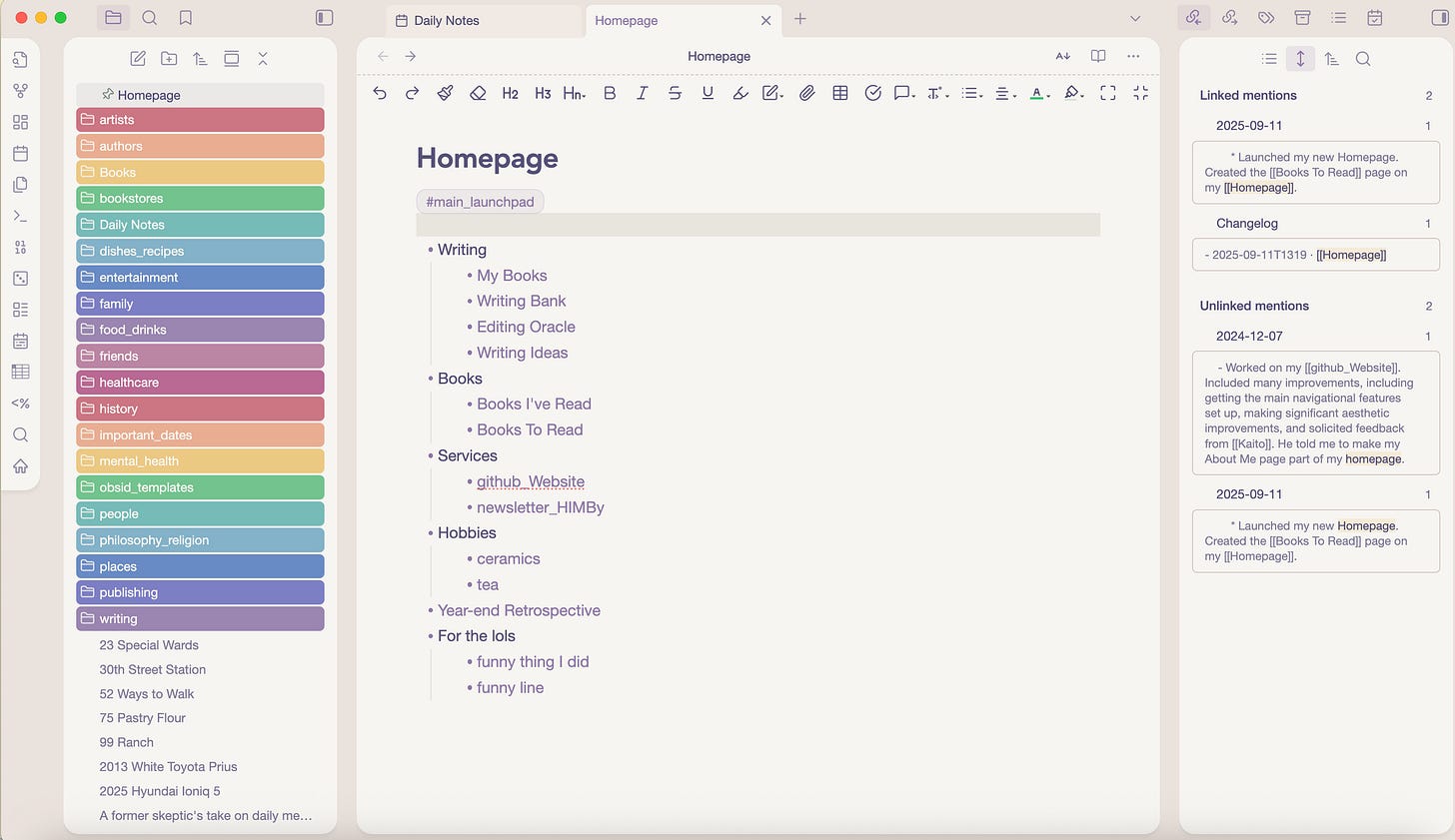

The first application I used to take notes was called Athens. Unfortunately, Athens folded after a year of using it, so I migrated to Roam Research. Then, at the beginning of this month and after extensive research, I switched ecosystems a third time to Obsidian. And it’s this final application, along with network-based note-taking that I’d like to discuss.

Before getting to the former, let’s start with the latter. Think about how you take notes. If you’re anything like past-me, it’s probably a combination of Stick-It notes wandering around your house, a few paper notebooks that may or may not be legible, and a somewhat organized system of thoughts in your computer’s default note-taking application. Trying to recall or locate information between these mediums isn’t easy, nor is making connections. For example, the Notes application on an Apple OS uses a hierarchical folder structure where every item you document lives in a silo.

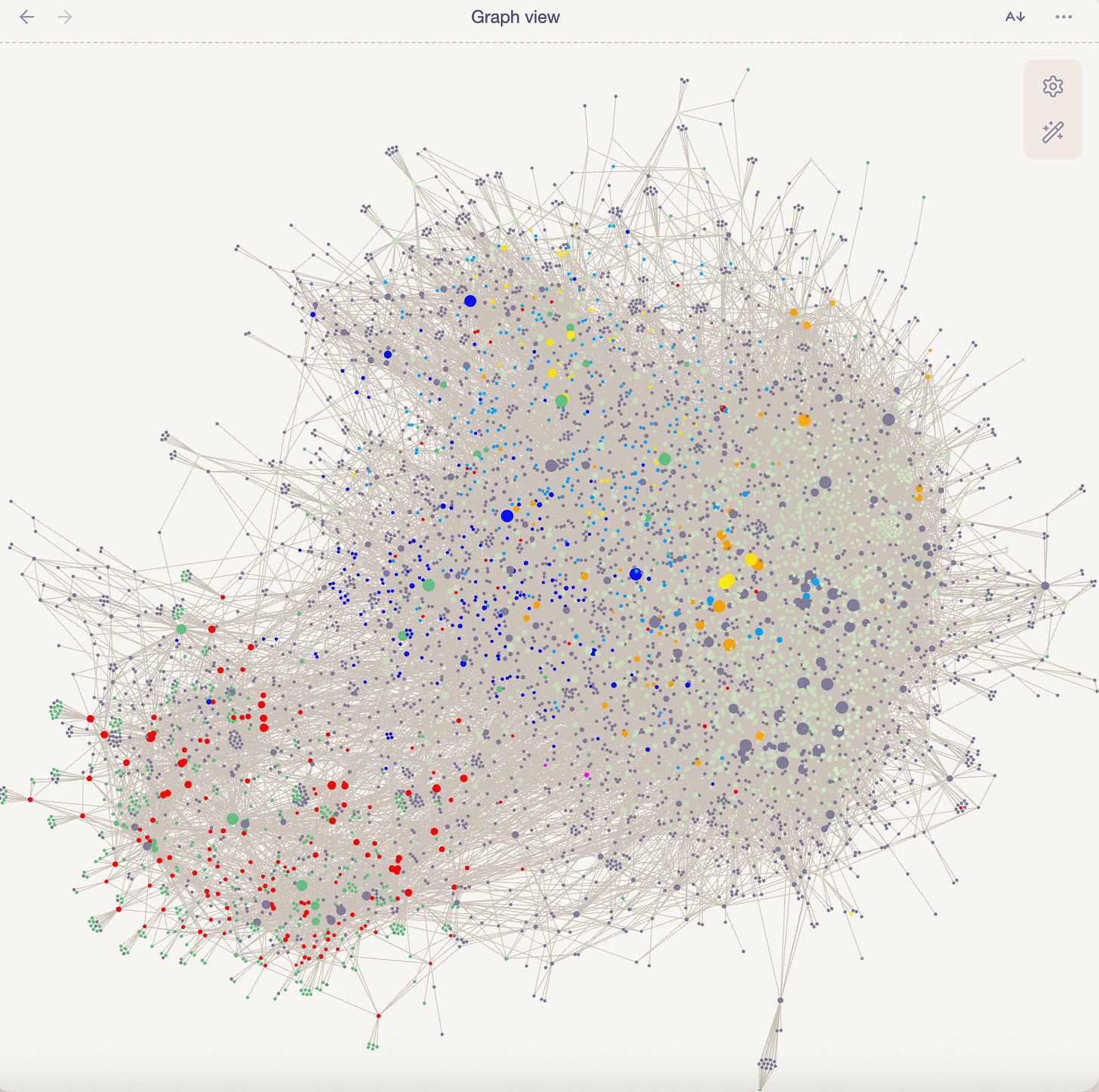

Network-based note-taking is the opposite approach to notes. Instead of a folder, you can imagine your pages of notes as a floating cloud of nodes and connections that exist in one system, like something akin to Wikipedia. What matters the most in this system are 1) the connections you make between concepts (i.e., internal links between notes), and; 2) how queryable the concepts are. Proponents of this system use David Allen’s terminology to describe your note-taking system as a “second brain.”

Obsidian is such a network-based note-taking application and the app I’d recommend above all others. Why is that? Because it’s free, future-proofed, and crazily customizable.

Obsidian stores your notes as markdown files in a folder of your choosing, whether on your device or on the cloud. Because files are markdown, they’ll open in any editor in the future, and you can edit them offline if you need. Nothing is locked behind a proprietary database, such as with Roam Research.

The folder structure of your doesn’t really matter so long as the app can access it—in fact, my notes’ structure emerged over time. Network-based note-taking encourages you to develop your own organizational logic, and because of the lack of hierarchical silos, it’s quite simple to change.

On your note pages themselves, you can use links (written in closed brackets like this, [[ ]]) to quickly connect ideas, where you can see how concepts relate. Maybe you’ve read a book about Proto-Indo-European and the sections on archeology reminded you of something you learned in another book, Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari. You’ve already written a lot about the latter, so by referencing [[Nexus]] on your Proto-Indo-European page, you’ve created that new relationship that you can return to at any time. Maybe you decide you’ll create some tags or custom metadata (YAML) for added clarity, too. Customization is Obsidian’s thing. The app offers a robust plug-in ecosystem, both from the developers and the community. You can install spaced-repetition cards, daily journals, Kanban, diagrams, custom visualizations, and many more things.

Network-based note-taking changed my life for the better in numerous ways. Through writing a daily journal, I learned to spend more mental time in the present, which in turn increased the quality of my life. I also built my knowledge base for topics I’d wanted to study for some time. Biology, for example, felt inaccessible to me before I started writing notes like this. Now, I’m easily building upon each biology book I read, linking concepts organically. And I use Obsidian to write these newsletters you’re reading now!

I linked the app above, but I’ll do so again here. I’d strongly encourage you to check it out—even if you’re mildly interested in taking notes.

Upcoming…

I’m a busy bee these days. Right now, I’m doing a line and copy edit sweep of my novel manuscript before I start to query this autumn. I’d still like to publish the second installation of my Deep Dive series on Constantinople, so I may hold off on a Cities post next week to get this puppy out to the paid subscribers. (If I have enough time, I’ll publish a Cities post, too.)

Until then,

Blake

Laura Spinney, “Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global,” (New York: Bloomsbury, 2025), 15.

Spinney, “Proto,” 18.