As a man who proudly calls California home, I don’t think I would’ve stuck around these parts in the year 1849. 1) I wasn’t alive in 1849, but; 2) even if I had been, I wouldn’t have jived with the “Wild West” vibes.

At its birth, the newfangled American state of California had no functional government and lawlessness was rampant.1 War had just ended—a large enough problem for a territory with so little infrastructure—and the strain on leadership was compounded by a sudden explosion in population. People from around the world flocked to California in search of gold, while the former Californios (residents of Spanish descent in the territory) either assimilated or left.2 Meanwhile, the first peoples of the land, the indigenous Americans, found themselves decimated by disease, captured, and forced into laboring for white ranchers. “The Indians of California make as obedient and humble slaves as the Negroes in the South,” wrote a white rancher, one Pierson Reading.3 (Side note: Reading, California was founded by and named after this man.)

Amid this chaos, the political leaders of the fledgling state needed to establish order. California required a constitution and a base of operations for the state government—a capital city. The Constitutional Convention of 1849 sought to solve these issues, where 48 delegates descended on the coastal town of Monterey to hash things out.

Alright, so California’s first constitution? Reference Iowa and New York’s constitutions. Check. And California’s capital city? Well… The delegates had encountered a slight problem: where to build one?

The Options

There were no major cities in California at this time. Believe it or not, the global metropolis of Los Angeles was then a dusty pueblo with around one-thousand people.4 San Diego, too, contained a smattering of homes and a Spanish-era Catholic mission. Even Monterey, the sometimes-home of the Spanish-turned-Mexican governors, proved unsuitable to the delegates of the Constitutional Convention.

If the coastal “cities” were too small, then where were the people? Thanks to the Gold Rush, most of the non-indigenous, non-church population had concentrated around the Bay Area and in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Boom towns like Placerville, Nevada City, and Auburn became hotbeds for fortune seekers, all three exceeding Monterey in size.5 (Nevada City was actually larger during the late 1800s than it is today.)

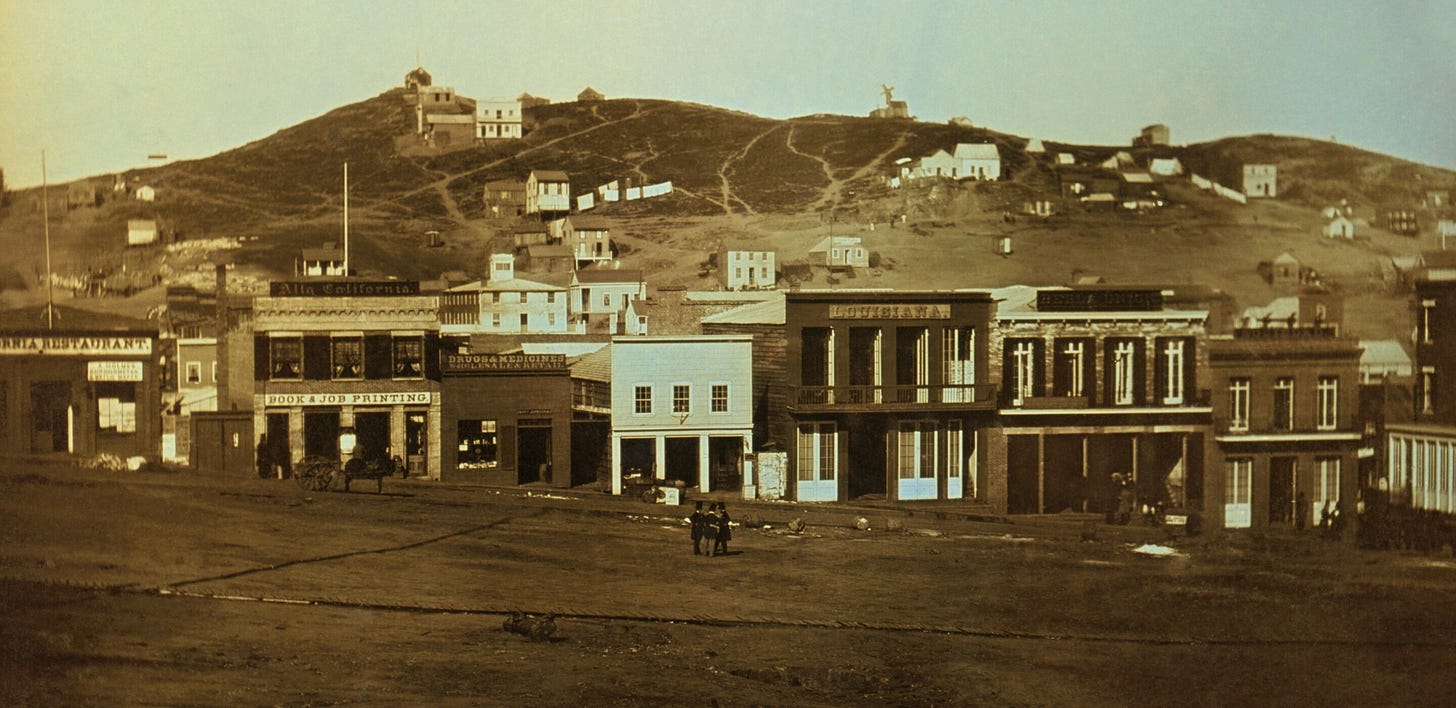

Perhaps the biggest boom town of them all was San Francisco. Rebranded from the name “Yerba Buena” in 1847, this windswept village housed 812 residents on the eve of California joining the United States.6 The Gold Rush changed everything. Rumors of gold in the east at first emptied the streets of San Francisco, but then the floodgates opened. The population soared to 25,000 full-time residents by 1850.7 For a while, it was the fastest growing city in the world. It was also a chaotic cess pit—muggings, bootlegging, and unregulated prostitution ran rampant. Not ideal qualities for a capital city.

The Choice

As the delegates debated what to do, two men burst into town. They were sent from the nearby town of San Jose, then known as Pueblo de San Jose. The men sold the delegates on an idea: to make San Jose the capital of California, of course. While San Jose was even smaller than Monterey or Los Angeles, the men argued that they had a site readily available for the Legislature to meet. Most of the delegates weren’t from California and had been in the soon-to-be-state for less than a few years. Persuaded by the bold sales pitch, the Convention agreed: “The first session of the Legislature shall be held at the Pueblo de San Jose, which place shall be the permanent seat of government until removed by law.”8

Thus, on November 13, 1849, San Jose became the capital of California, even before California official statehood in 1850. The town was around the same size as San Francisco in 1847, but hadn’t experienced the same Gold Rush population boom.9 It was nestled at the bottom of the San Francisco Bay, south of the migration to the Sierra Nevadas—still accessible, yet also defensible from seaborne attacks should that ever be necessary.

The promised site for the First Session of the Legislature turned out to be a two-story adobe hotel. The Assembly made use of the upper story, while the Senate occupied the lower story. According to first-hand accounts documented by the State of California, the accommodations were—um, not great. “The Senate… occupy the lower apartment, which is a large, ill-lighted, badly-ventilated room, with a low ceiling.” Legislators immediately began to complain about both the Capitol and the general lack of amenities in San Jose, and call to relocate grew.10

General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, a key man in early Californian politics, proved to be the death knell to San Jose’s short existence as the state capital. A Californio, General Vallejo had been born a Spanish subject, served the nation of Mexico, and then remained a central figure in the formation of the American administration. His family significant landholders in the region, making him one of the wealthiest men in California. Equally frustrated with the inadequate quarters of San Jose, General Vallejo offered the Legislature a generous plot from his estate, northeast across the waters from San Francisco. The Legislature happily accepted his offer.

On February 4, 1851, less than two years after the Constitutional Convention of 1849, California relocated its capital from San Jose to the new town of Vallejo. It would take two more attempt before a permanent location would stick—Vallejo and Benicia, California’s third capital, suffered from flooding and size constraints, respectively. In 1854, the Legislature relocated the capital a third time to Sacramento, where it remains to this day.

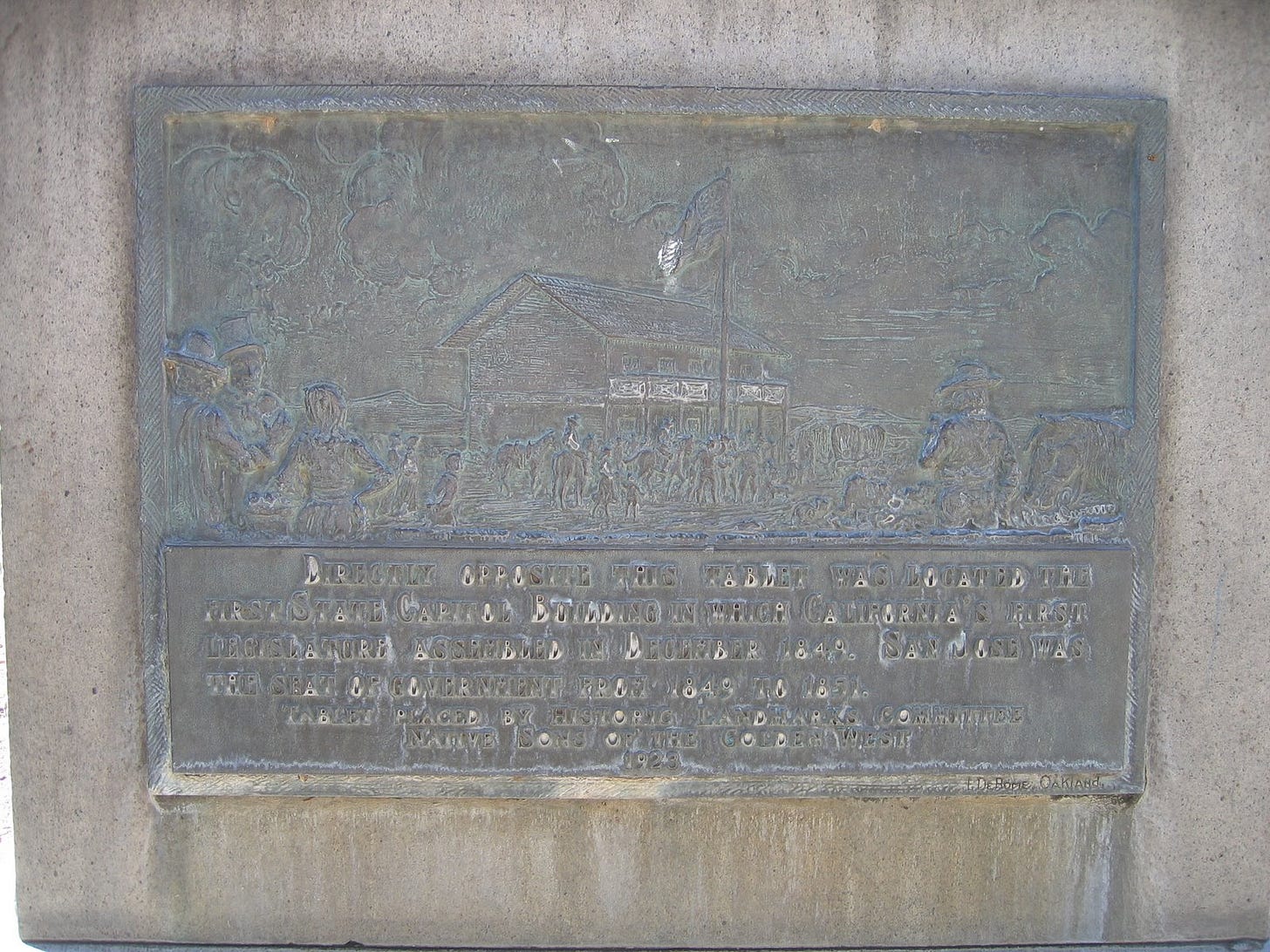

Having visited San Jose a few times, I’d never seen nor heard of a capitol building, nor anything else indicating its history. I decided to conduct a little search for evidence, and came up with an interesting footnote with which to conclude this post. The adobe hotel where the First and Second Sessions of the Legislature met no longer exists, but it turns out that there’s a building marker where it once stood. The plaque rests in the Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose. I’ve (ironically) driven past this monument without even noticing, but that’s appropriate given San Jose’s short-lived stint as the first capital of California.

John Mack Faragher, California: An American History, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022), 178.

Faragher, California, 169-70.

Faragher, California, 176.

Census, 970-1.

J. S. Holiday, Rush for Riches: Gold Fever and the Making of California, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), 51.

James J. Rawls and Richard J. Orsi, eds., A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), 187.

Constitution of 1849, Article XI, Section 1.

Holiday, Rush for Riches, 51.

Northern California Writers’ Program, Works Project Administration. California’s State Capitol, (Sacramento: Office of State Printing, 1942), 31.