Just a friendly warning: while this article contains a lot of hope and courage, I will discuss the human suffering caused by the atomic bomb. The section will be labelled “The Day Hiroshima Was Destroyed,” so if you’re not in the mood for something so dark, please feel free to skip that section.

In late May 2025, I visited Hiroshima for the first time—and only for one day. Unlike the image above, it was pouring rain when I arrived by ferry from Matsuyama. It’s true that I toured the city soaked to my underwear, but I had a fantastic time. The people were warm, the authentic, Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki proved the perfect remedy for being wet/cold, and the city was alive with bright lights and cute street trams.

Hiroshima now ranks as Japan’s eighth largest metropolitan area,1 a commercial hub of over 2 million people that attracts the same annual number of tourists (like me) from around the world. Its the most prosperous the city has ever been. Yet, most human beings alive today know one basic fact about the city’s past. On August 6, 1945 at 8:15 a.m., the United States military dropped an atomic bomb over the Hiroshima.

The Day Hiroshima Was Destroyed

The bomb detonated a little under 2,000 feet above the Shima Hospital. Dr. Shima himself was away from the city with an attending nurse, but all 80 of his staff and patients were instantly incinerated.2 On detonation, a heat wave of almost 4,000°C (7,232°F) roared through the city, carried by winds that topped 1,440 feet per second, obliterating everything in its path. The U.S. military murdered3 80,000 people—men, women, and children—immediately, whether by the blast or subsequent fires, but by the end of the year, injuries and radiation poisoning brought the death toll to 140,000, over one-third of the city’s population. The stories passed to us are gruesome. Victims staggered through streets with skin sloughing from their arms and faces, pleading for death, or collapsed in rivers in search of water, only to perish there.

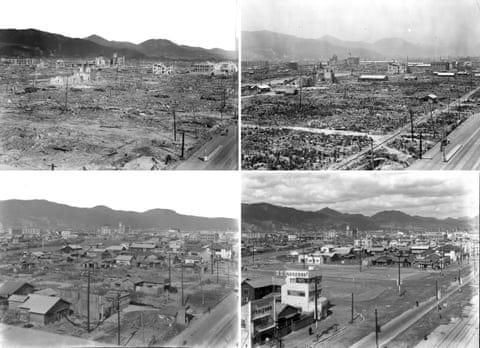

The physical damage to the city was near total, too. According to a document from the Hiroshima Prefecture, Japanese survey estimates showed that about 92% of the city’s 76,327 structures were destroyed.4 Additionally, 40% of Hiroshima’s usable land area had been scarred and wasted; water, power, trams, telephones, and hospitals ceased to function in a heartbeat. The city became ash.

Resilience & Rebuilding

Oftentimes, stories of Hiroshima’s “fate” end there with the city’s nadir. Yet, within 24 hours, volunteers and remaining officials improvised relief posts. Power returned around the Ujina Line on 7 August, and to the train station a day later. Three days after the bomb, within hours from when Nagasaki was destroyed by a plutonium bomb, survivors rolled one battered streetcar back onto its tracks, a promise that the city would revive. (By the way, I learned while visiting the city that two vehicles survived the atomic bomb. The Hiroshima Electric Railway refurbished them and they’re still in operation today.)

Survivors, demobilized soldiers, and volunteers from nearby prefectures cleared debris, salvaged bricks, and erected improvised stalls that morphed first into a thriving informal market around Hiroshima Station, and then formalized public and private spaces.5 The Bank of Japan’s local branch—roofless but standing—re-opened two days after the attack and hosted eleven other homeless banks under makeshift tarpaulins, ensuring that survivors had access to money. Dr. Shima returned to the city to discover the fate of his staff and patients, but then stayed. He slept in the nearby bank that had not collapsed and worked to treat the injured survivors, who rested at Fukuromachi Elementary School (160 elementary school students and teachers had burned to death in the bombing, but the basement remained habitable). Dr. Shima rebuilt his hospital in 1948 on the same site as the first iteration, and the hospital still exists to this day with Dr. Shima’s grandson as the current director. Such gestures of mutual aid filled the leadership vacuum left by the mayor’s death and the loss of 90% of municipal employees.

National legislation soon caught up with on-the-ground improvisation. The Special City Planning Law passed in September 1946 mandated every ruined city to file a rebuilding blueprint. Hiroshima submitted its plan that November. In 1949, the landmark Peace Memorial City Construction Law granted Hiroshima state land pro bono and subsidies in recognition of its unique suffering, while also sparking an international design competition for a first-of-its-kind peace park. Pritzker-winning architect Kenzō Tange won the commission, envisaging a 100-meter-wide Peace Boulevard and a tree-covered memorial park straddling the hypocentre, anchoring the cityscape in a symbol for peace. You can see the Hiroshima Peace Park in the titular image of this post.

Rather quickly, the city sprung back to life. One-third of the roughly 60,000 homes destroyed by the bomb had been rebuilt by the turn of the 1950s, although in a Western style perhaps influenced by the American occupation. The Korean War (1950–53) and the lifting of a shipbuilding ban in 1952 injected fresh capital into Hiroshima, reviving local industries from canned food to heavy manufacturing. Mazda Motor Corporation (albeit founded under a different name) was a pre-war company in Hiroshima and remains headquartered in the city to this day. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Ryobi Limited have also provided generations of significant employment.

These booms helped Hiroshima’s population surpass pre-war levels by 1958—a mere thirteen years since its destruction. By 1970, the city’s population had quadrupled.

Conclusion

The city’s rebirth was neither automatic nor inevitable—it was hammered into being by neighbors providing shelter and food, by planners who turned ground zero into a peace park, and by lawmakers willing to fund a vision rooted in memory rather than amnesia. Most survivors are now in their eighties and nineties. Soon, the bombing of Hiroshima will pass from living memory, and the remnants of the past that I witnessed on a rainy May evening will be all that’s left. Hiroshima’s lesson, eight decades on, is that even in the shadow of unimaginable horror, human resilience can coax a shattered place back to life.

Statistics Bureau of Japan, “データセット一覧” (Japanese language), https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001080615&cycle=0&tclass1=000001110216&second=1&second2=1&.

Hiroshima Peace Media, “Shima Hospital” (Japanese language), https://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/abom/99abom/kiroku/saiku/shima.html

I am not writing this to comment on the “necessity” of using atomic weapons to end WWII, an argument I’ve heard more than once in my life, nor am I writing this to paint the U.S. military as black-and-white evil. I simply use the word “murder” because it’s a fact: the U.S. government engaged in a premeditated strike on Japanese civilians with the intent to kill (which they’d been doing for some time at this point in the war, having fire bombed over 200 cities). They used a nuclear weapon on civilians again three days later at Nagasaki. You are welcome to interpret these facts as you wish—I’m simply stating in the open what is often danced around when discussing this history.

Hiroshima Prefecture and The City of Hiroshima, “Hiroshima’s Path to Reconstruction,” (2025): 7. https://www.pref.hiroshima.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/611929.pdf

“Hiroshima’s Path to Reconstruction,” 19.